A recent Leaders Virtual Roundtable explored five common trends on talent development pathways.

With those questions ruminating in Leaders Performance Institute members’ minds, Luke Whitworth, our Sport Performance Team Lead, set the scene for a discussion of current trends in athlete development at youth level.

The group highlighted both trends and their attendant challenges, yet there was a sense that these also represent opportunities to refine how coaches and practitioners approach talent development.

These are the five main trends that stood out from the conversation, as well as some ideas that have served members well in their roles.

1. The provision of holistic development is a baseline expectation

“We’ve been growing when it comes to holistic development,” said a coach from a Middle Eastern academy, “not only the focus on the technical, tactical part, but also performance in the physical area, the psychological support, the educational programmes.”

It’s a situation that extends well beyond that region and it is not just the athletes but their parents who demand more rounded support.

“It is very important to be on the pitch with the players and in the dressing rooms, the lecture rooms, because it’s important to work directly with them and support them,” the coach added.

Opportunity

A psychologist based in the Australian system shared her approach:

“We have dedicated programmes and an evidence-based curriculum that teaches those skills of resilience, coping, receiving feedback and the soft skills.”

2. Earlier professionalisation

Young athletes in team sports increasingly come with their own performance entourage in tow – physios, S&Cs, psychologists – and it’s led a shift towards a “more professional mindset and approach”, as a coach based at a British university describes it.

“We’re now working in performance, not development,” said another. This expanded menu of support services is not a bad thing in isolation.

“From a coaching point of view, the influence they have on feedback that the player gives you is not necessarily aligned with what we’re trying to implement as coaches; and that can be frustrating,” said a coach at an AFL club.

Those influences include third parties, such as agents. “We actually have services that are professional organisations that just provide services for athletes who are on their way up and they cherry-pick them,” said a performance director of the Indian sporting landscape where he plies his trade. “They give them a psychologist, a physio, a strength & conditioning person and everything else they need as soon as they get a whiff that they might be talented.”

Opportunity

Compromise and clarity are essential, as the India-based performance director explained:

“As an academy we have to make agreements, establish roles and responsibilities, who should take care of this, who should take care of that, while we’re managing that professional approach.”

3. Many young people are priced out

As the price of attending both training and competitions year after year continues to rise, those from less affluent demographics are falling away.

“How can we get people who maybe can’t afford to get into these sports to stand in front of us?” said a head of youth coaching at a major English football club. “Our academy car park is amazing. It’s like a first-team car park. The days of kids coming on trains and buses to training have almost gone now.”

Opportunity

In Australia, some sporting bodies support and subsidise athletes; and if a child in a remote region requires online assistance to make it work, then that’s what they’ll receive. The aforementioned psychologist said:

“We’re very conscious of setting up a pathway that players can access equitably. We don’t charge to come on a talent camp… and we’ve just sent a player off for an MRI. We’ll pay for that. We pay for their accommodation and their food, which is probably not common across pathway sport or teenage sport in Australia.”

4. Changing athlete psychology and social needs

This is related to No 1. Today’s young athletes are often more technically skilled than previous generations, but they require more psycho-social and emotional support.

For one, young athletes today are more extrinsically motivated, as the head of youth coaching in English football observed.

“They really care about what people think of them, the perception piece, whether that’s social media, but they really care what people think about them. So being part of a group is quite important for them,” he said.

On that final point, the same scenario is playing out in Australia. “The one thing I’m sensing now is the expectation of a player that’s been at the club for a while or just coming in is that they feel connected to the environment,” said the AFL coach. “So if that doesn’t happen, we’re seeing more player movement than ever before.”

Opportunity

Players are taking more care in their choices rather than pledging blind loyalty to a club – and the smartest teams have noticed. “We’re actually seeing the greatest successes in terms of who wins the premiership or the championship from teams that do that well compared to ones that don’t,” he said before adding:

“The athlete is putting a lot of time into making decisions about their careers. I think we’ve got to step up in this space and not be walked over by the athlete, but understand what their motivations are and tailor it to the individual as much as anything. I know the social skill part is an ongoing challenge. I’ve already had older players come up to me and going ‘he’s not fitting in well socially’. So we’ve got to go to work on that.”

5. This all means that staff members must change

As the conversation neared its conclusion, Whitworth posed another pertinent question: “We’ve talked a lot about how the athlete is evolving, but in turn, how do we have to evolve as well? And what additional skills are we going to need?”

Communication, as ever, was high in the group’s thoughts. “Everyone’s gone digital first,” said a sports nutritionist based at a British university. “I probably do 80% of my work with athletes online.”

His colleague, a coach, concurred. “When there’s clarity then there’s clean execution from different disciplines. When it’s muddy, things don’t get done.”

Opportunity

The performance director based in India went further based on his experience:

“We have to become diplomats, high‑level development people who can manage such diverse groups. Somewhere along the line, we need to start creating those development opportunities for everybody who’s on this call.”

What to read next

Talent ID and Development: The Race to Deliver Formula 1’s First Female World Champion

29 Jul 2025

ArticlesEdd Vahid of the Premier League has advice for coaches and athletes alike.

So says Edd Vahid, the Premier League’s Head of Academy Football Operations.

The numbers as revealed in our Trend Report back him up. Almost one in five practitioners who completed our survey felt that learning and development had a direct impact on the quality of leadership in their teams.

“It has to come from senior leaders, it must be role-modelled from the top,” Vahid adds. “Role models are crucial in setting the tone for organisational learning.”

When it comes to teaching and learning, he has advice for coaches and athletes alike.

For coaches

Create the right environment…

The skill of the teacher, coach or trainer is to create an environment where you’ve got the capacity to learn, to receive feedback, and for it not to be immediately critical.

That means creating opportunities…

If you’re learning and you’re able to apply it, you’re going to see progress. You need the opportunity to because therein lies the application of knowledge.

You must also work to understand how people learn…

I think we could probably spend more time on this as an industry. To support an individual, you need to understand an individual, to understand an individual, you need to invest time in them. People learn where there’s been care, an attentiveness, and an investment in the person. The coach needs to understand what makes someone tick beyond the superficial level. What are their influences? What is creating an impact on them when turning up to do a session? What’s going on at home? Such considerations are crucial.

Also ask yourself: what are you trying to achieve?

What outcome are you trying to achieve? That will determine the approach, timing and future support. If you simply use feedback as an opportunity to offload, especially when a learner hasn’t done well, it may serve your benefit because you’ve been able to get rid of some of your frustrations. But that’s not right. To help them, you have to offer them something they haven’t seen themselves or it’s going to drive them further down.

Enable good feedback loops…

It starts with an expectation. The feedback is specific to that expectation. Then identify what the development opportunities are. So how do you avoid or improve a certain situation in the future? Then there’s the monitoring.

Inviting people to share their feedback on the process is an important part of the feedback loop. The best coaches plan but they’re also responding to emerging themes and the needs of players within a particular session. It goes back to understanding the player’s needs and considering those in session design. We probably don’t seek their feedback often enough. Ask simple questions: how is this working for you? What’s landing? What influences that? Are you progressing?

For the athlete

And learners must be adaptive…

We each have our learning preferences – others will be better equipped to talk about the myths that surround learning styles and other elements – but you have to find a way to respond to the stimulus in the environment. If you haven’t had opportunities how are you going to accelerate your learning without the chance to compete?

That means there has to be personal responsibility…

You see it all the time: the highest performers, whether implicitly or explicitly, go out of their way to make sure they’re ready to learn. There has to be personal responsibility when it comes to how you turn up to learn, how prepared you are to absorb the information that’s available in the environment, whether that’s through players, coaches or other ways. You must be prepared to learn.

What to read next

10 Jul 2025

ArticlesIn a world where they don’t know ‘what it takes to win’, Fran Longstaff and More Than Equal are ‘building the road as they walk’.

Fran Longstaff, the Head of Research at More Than Equal, reminds the audience at April’s Leaders Meet: The Talent Journey that no woman has competed in a Formula 1 race since the Italian Lella Lombardi in 1976.

This is despite motorsport being one of the few mixed gender sporting domains where men and women can compete on equal footing.

“Our research rates show that females make up ten per cent of participation rates in motorsport,” adds Longstaff. “That goes down to four per cent at the elite level.”

More Than Equal’s mission is certainly bold. The organisation was founded in 2022 by former F1 driver David Coulthard and philanthropist Karel Komárek, The pair recognised that even the most accomplished young female drivers are behind on the development curve compared to their male peers.

Longstaff was drafted in to better “understand the problem behind the problem”. “Research and data runs through our Driver Development Programme like a stick of rock,” she tells the audience at the Royal College of Music. This approach is critical when the end point is still unknown.

The programme itself is divided into four pillars:

Their search began in karting. They trawled through the race results in a sport where it is notoriously hard for girls to take the next leap.

“That sounds like an easy task but karting race results are often stored as PDFs,” says Longstaff. “It is objectively the worst way to store data.” They also had to gender mark race results, which took time.

Additionally, more than 500 young female kart drivers heeded More Than Equal’s call to apply for their Driver Development Programme. The drivers with the most potential were invited to follow-up interviews, which extended to parents and families. “That way we could understand what activity they’d already done to enable them to get the results we were seeing on the track. This is where you could have some interesting conversations and even say the driver was over-performing their level of activity in that sport.”

Six drivers, all aged 13-14 years old at the time, made it into More Than Equal’s first cohort:

To understand the problem behind the problem, More Than Equal, produced its Inside Track report in 2023:

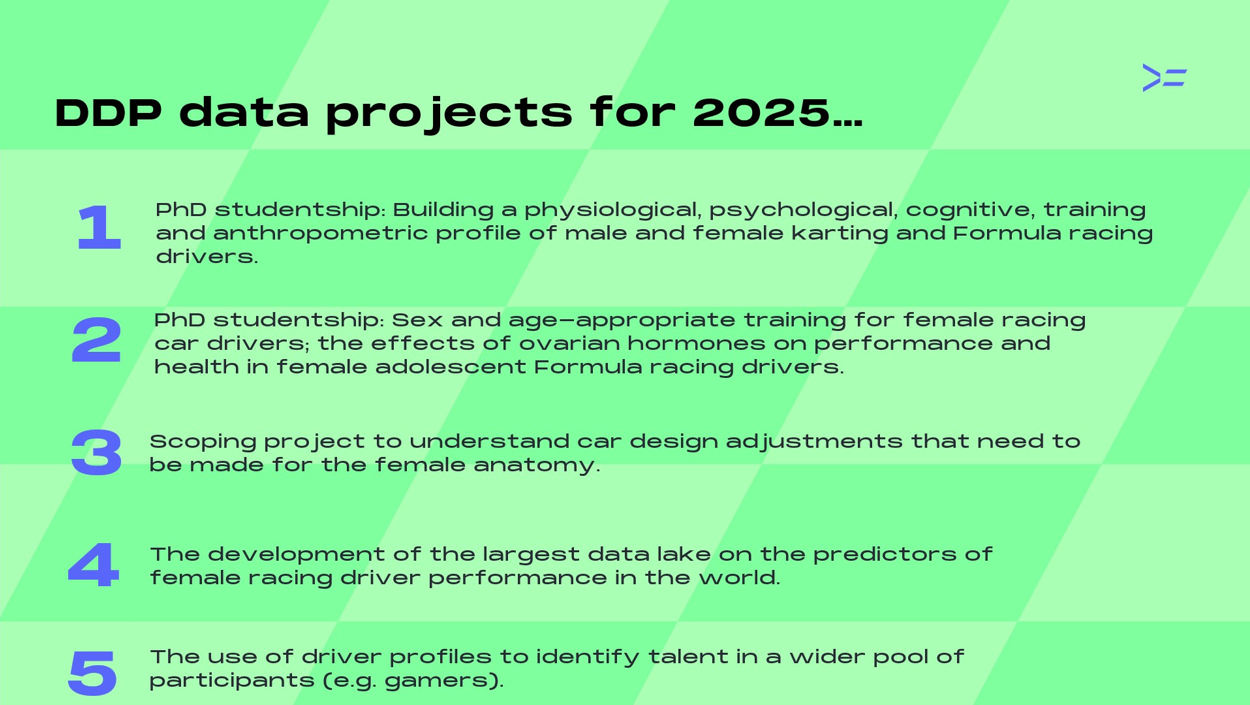

“There were fewer than 30 research papers on the human factors related to driver performance,” says Longstaff, who explains that they are “building the road as we walk”. Data is even more scant when it comes to female drivers or their experience behind the wheel. “We’re looking at how we can optimise and adjust cars to ensure that females can perform at their best without being hindered.” Longstaff underlines that this will not come at the cost of performance decrements to the car.

Additionally, the Driver Development Programme takes a 360 approach, taking in the physiological, psychological and technical elements of racing in an effort to better address the difficulties young girls face in karting. “We want to make that transition as seamless as possible,” says Longstaff.

There are regular coaching contact points. “We have camps every six to eight weeks where we come together as a community.” The girls recently had the opportunity to spend time with Coulthard at the Red Bull Ring in Austria. “They asked a lot of questions about his experiences and could really start to understand what it is to be an elite racing driver.”

Longstaff also explained that More Than Equal’s research is freely shared with F1 teams, which is a break with the usual secrecy that governs their interactions.

Benchmarks simply don’t exist for female F1 drivers. “We don’t know what a racing car driver should be doing and look like at 16 versus 18,” says Longstaff.

More Than Equal has commissioned two PhD students at Manchester Metropolitan University to help establish those benchmarks. “One student is going to be building physiological, psychological, cognitive training and anthropometric profiles from drivers all the way from karting to F1.”

The research into male and female differences will kick all tired and unfounded assumptions about female drivers into the long grass.

The other PhD student will research how hormones impact performance, particularly when it comes to cognitive function.

This work will help More Than Equal to build was Longstaff calls “the largest data lake on the planet on the predictors of female racing driver performance”. She adds: “All of those PDF race results get pulled into one central pool and we start to overlay that with the physiological, cognitive and psychological data. Once you have that, you can start to make predictions and we can understand who may have a greater chance of success at the next level of competition.”

It will also help to widen the talent net. “Once we have these driver profiles, we may be able to start to understand whether there are certain populations where we can spot talent.” Longstaff suggests the world of esports. “It’s a 50-50 split in terms of male-female players, so there’s a huge population we might be able to pull from.”

On top of that, digital twinning technology has the potential to enable teams to optimise how they adjust cars to the needs of their drivers with recourse to expensive testing. “You don’t necessarily need to be on the track,” says Longstaff, “but we can only do that by having all those data points in one system.”

What to read next

‘Some Skills of Adaptive Leadership Are Obvious, But That Doesn’t Make them Easier to Learn’